Permanent Home of the

ANONYMOUS SHIVA LINGA PAINTINGS

HUDSON COLLECTION

IOWA CONTEMPORARY ART

The Hudson

Collection

More about the Hudson Collection

This inaugural installation in ICON’s Hudson Collection Gallery features the Anonymous Shiva Linga Paintings

exhibited at the 55th Venice Biennale, curated by Massimiliano Gioni, artistic director of the 2013 Venice Biennale and

associate director of the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York. For the Biennale installation, Gioni selected

31 paintings from the series of 71 Anonymous Shiva Linga Paintings assembled by Franck André Jamme and

Feature Inc., New York. ICON’s exhibition duplicates the selection and sequence of the paintings at the Biennale.

The Shiva Linga is an abstract or aniconic representation of the Vedic god Shiva as an eternal cosmic pillar of fire,

the first and final form of all creation. The three-dimensional stones and two-dimensional drawings of the Linga are

considered by devotees to be not mere representations of Shiva but rather the sacred embodiment of the Divinity.

These Shiva Linga paintings on found paper are made anonymously in India (primarily in Rajasthan) by practitioners

of Tantrism—some of whom are artists—to represent and embody fundamental aspects of Tantra, a vast and complex

spiritual and philosophical practice. Made to awaken heightened consciousness, these devotional images are used for

visualization and meditation as part of Tantra’s spiritual practices. While the images are centuries old with highly

codified forms and colors, the paintings are filled with such a high level of the artists’ intentionality that they continually

appear fresh and alive. The French poet/scholar André Padoux has described these images as “painted silences. . .

the simple revelation of pure consciousness.”

According to French poet Franck André Jamme, who has played an instrumental role in bringing these paintings to

western audiences, the tantrikas who create them work in a focused state of mental rapture. Despite their expression

of an unbroken, centuries-old tradition, the works in this exhibition (made between 1966 and 2004) seem both timeless

and utterly contemporary. They also possess a remarkable affinity with examples of twentieth-century abstract art.

The progeny of hand-written, illustrated religious treatises from the seventeenth century, copied across many generations,

these paintings are part of a distinct visual lexicon that confounds assumed differences between East and West, the

spiritual and the aesthetic, the ancient and the modern.

This exhibition is dedicated to the memory of Hudson, founder and director of the New York art gallery Feature Inc.

The Hudson Collection has been very generously donated to ICON’s permanent collection by Patricia Hudson,

James Hudson, and Thomas Hudson.

IOWA CONTEMPORARY ART | 58 North Main Street, Fairfield, IA 52556

641-919-6252 | bill@icon-art.org | iconbillteeple@gmail.com

GALLERY HOURS: Tuesday through Saturday, 12:00 to 5:00pm and by appointment.

ICON is an IRS 501(c)(3) non-profit educational charity. All donations are tax-deductible.

Excerpts from Franck André Jamme’s last interview, September 2020,

“Only This Glow Remained” (by Amy Hilton, TL Magazine)

TLmag: You have travelled many times to India. Let us circle over to these

extraordinary abstract Tantric paintings that you are known for introducing into the

West. How did you discover them?

F.A.J.: I first discovered them through literature. Originally, it was at a bookshop in

Paris where I found a small gallery catalogue about an exhibition that had been held

some years before. The catalogue opened with two texts: one written by Henri

Michaux, the other by Octavio Paz. I discovered something existed in India that was

totally abstract, with such simple shapes and symbols, inside such a baroque

culture. I absolutely wanted to know more about this Tantric art. But I realized that

there was next to no information published about the meaning of these paintings.

So, I decided to go to India in search of them. But the first few trips were

unsuccessful. It took twenty years for us to find each other.

TLmag: Why so little information?

F.A.J.: Because of bad climate conditions, monsoons, rats, insects, careless

conservation… not many survived. Certainly, some of these paintings did exist

before the 17th century, but we don’t have proof of that. And, even the Indians don’t

have real access to Tantrism itself. It is a kind of small secret society in Hinduism. All

is enriched by secrets and a hidden world.

TLmag: Tantrism, as it is known in the West, has been used in quite diverse ways

throughout history to mean various things for different people. It defies easy definition.

F.A.J.: Tantrism is so deep. And, yes, it is not very well understood in the West.

Because, as usual, Westerners think about the parts of it, which often have a close

relationship with sex or eroticism. This is a very important point: a body of thought

that has cosmic sexuality included at its own heart. But there are so many other

parts to it. There is a main part of it about language. The mantras. The Tantrikas are

the kings of mantras. This became so interesting for me. Because of the language.

TLmag: I have read that the ‘way of Tantra’ involves a highly individuated personal

research enquiry: a personalized ontological journey. Essentially, each person finds

her or his own ‘way’.

F.A.J.: You know, I was very lucky. Because a terrible thing happened to me on my

way. On one of my research trips in India I was involved in a terrible road accident

where the bus I was traveling in hit a lorry coming the other way. Around me, almost

everyone died. And the irony of the thing is that I would not have had any access to

the families who were making these little wonders without this accident. It opened

another door… After the accident I was petrified of going back, but with the help of

some friends in Paris, I decided to return three years later. A friend told me to go and

see a soothsayer. A sort of guru. I met the man, and it was one of the strangest

meetings with another human being I have ever had in my life. He looked like a fox.

Really. A pure fox. I told him I wanted to continue my research, but I was so terrified

to do so. He asked me to wash my hands in a large jar of sand. He stared at the

patterns and read the shapes in the sand, made by my hands. They do that in Africa

also. It is a kind of divination… And then he told me that I had paid my tribute to the

deity, to the goddess. He told me I could go ahead with my research. But secretly. I

could show these paintings in the West, but on two conditions. First condition, I

could sell the pieces but only for enough to earn my own living, not to become rich.

Second condition, he said when I would go to meet the families who were making

this art, I must go alone or only with the one I love. He was standing at the door with

a foxy smile and, just as I was about to leave, he wrote down two names and

addresses on a little piece of paper, and kindly handed it to me. I truly thought that I

was going to leave without what I was supposed to find. But he handed me the key.

And I immediately went to the first address. And so, it began like that.

TLmag: Can you expand on the creation of these paintings?

F.A.J.: They were originally illustrations that accompanied hand-written manuscripts.

Over time, they were copied out separately from the texts. Their purpose was to be

used as tools to meditate, to connect with cosmic forces in the larger universe. It is

important to remember that they are made anonymously by people who would not

describe themselves as artists. They do not think for a minute that they are artists…

They are just continuing the tradition of the family. What is so inspiring to me is that if

I send them a commission for a piece, I sometimes receive it one year later. There is

absolutely no rush for them to receive money quickly. And I love that. I really love

that. It is very important for me. They do not react quickly at all. Another thing that

inspires me – this is not at all a patriarchal tradition. There are so many women

painting these pieces. And this is so rare in India. As they are anonymous, we would

never know this.

TLmag: They are so akin to poetry. Visual poetry. I am interested in the actual spark

of creative transmission. These simple geometric shapes: ovals, squares, circles,

triangles. The choice of colours…

F.A.J.: They paint them according to an endless schema, constantly repeated and

passed on from generation to generation in each family. Like a raga in their music –

you start with the scale and then improvise. You have five or six notes for one raga,

but you can play it as you like. You just need to respect the original five or six notes.

They do not vary too much.

When they make these paintings, it is also very much like Indian music – it depends

very much on a feeling at a certain moment, on their inside mood. They are not

going to paint a very powerful and red image if they are in a breezy mindset, if you

know what I mean. It is an inner gesture each time.

TLmag: “Never in the universal history of painting,” you once wrote, “have works

been produced that are both so mysterious and simple, so powerful and pure… a bit

as if, with these works, man’s genius had been able to assemble almost everything

in almost nothing.” They are jarringly affective.

F.A.J.: They are. They vibrate. A Shiva Linga on fire. So full of energy, it is burning.

TLmag: Curiously, I do not see one of them exhibited here in your house.

F.A.J.: It is funny, but yes, I do not have a single piece on my walls. Because

I have been very prudent with these pieces, you know. In a sense I do not want to

show them too much. And certainly, I do not want to see them too much. In a very

strange way, I do not like the idea of possessing them. They are much stronger than

me. They could possess me, but I could not possess them. I do my best for them.

They know that I have done my best for them, for a long time now. They are friends.

Maybe I need their energy. Perhaps they could help. Nevertheless, I am so happy to

have met this art. You have no idea how truly happy it has made me.

14. David T. Hanson and Allen Cobb, Slide Show

Anonymous Shiva Linga Paintings/1,000 Names of Shiva,

2014/2017, HD video, color, sound, 48 minutes.

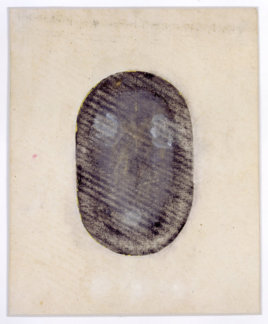

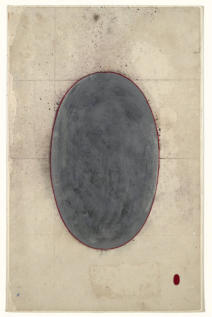

All of the paintings below are anonymous and untitled. The artists use various media

(watercolor, tempera, gouache, ink, hand-made colors) on found paper. The location of the

artist in India, the date of the painting, and the dimensions are listed below.

(Click on images below to enlarge.)

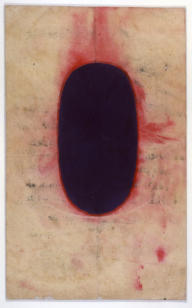

1. Anonymous: tantric painting, Shiva Linga, 1966, Udaïpur,

unspecified paint on found paper, 12¾ x 8¼".

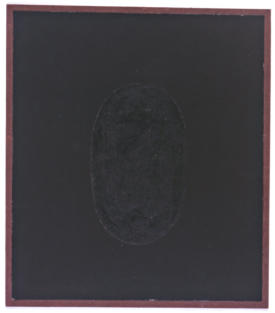

2. Anonymous: tantric painting, Shiva Linga, 1975, Udaïpur,

unspecified paint on found paper, 12 x 9¾".

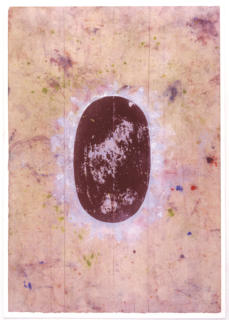

3. Anonymous: tantric painting, Shiva Linga, 1970, near Udaïpur,

unspecified paint on found paper, 16 x 10¾".

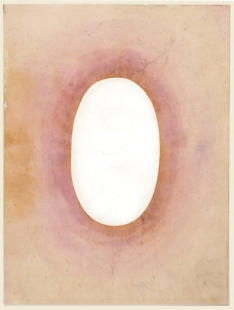

4. Anonymous: tantric painting, Shiva Linga, 1979, Udaïpur,

unspecified paint on found paper, 13¼ x 8¾".

5. Anonymous: tantric painting, Shiva Linga, 1981, Udaïpur,

unspecified paint on found paper, 12½ x 9½".

6. Anonymous: tantric painting, Shiva Linga, 1982, Udaïpur,

unspecified paint on found paper, 13 x 10¼".

7. Anonymous: tantric painting, Shiva Linga, 1993, near Udaïpur,

unspecified paint on found paper, 13½ x 8¼".

8. Anonymous: tantric painting, Shiva Linga, 1994, near Udaïpur,

unspecified paint on found paper, 13½ x 9".

9. Anonymous: tantric painting, Shiva Linga, 1995, near Udaïpur,

unspecified paint on found paper, 13¾ x 8¾".

10. Anonymous: tantric painting, Shiva Linga, 1995, Udaïpur,

unspecified paint on found paper, 12 x 10½".

11. Anonymous: tantric painting, Shiva Linga, 1996, near Udaïpur,

unspecified paint on found paper, 14½ x 10¼".

12. Anonymous: tantric painting, Shiva Linga, 1999, Udaïpur,

unspecified paint on found paper, 13 x 8½".

13. Anonymous: tantric painting, Shiva Linga, 2000, Udaïpur,

unspecified paint on found paper, 12¼ x 9¼".

The French poet Franck André Jamme first encountered South Asian Tantra

paintings in 1970 in an art gallery in Paris. Jamme was fascinated by these paintings

that were so close to Western modern art, from Kazimir Malevich and Paul Klee to

Agnes Martin and Daniel Buren, and many others. During the subsequent years,

Jamme discovered books on Tantra art (especially those by the eminent curator and

collector Ajit Mookerjee), and he decided to try to find the artists who were creating

these works. Following several unsuccessful trips to India, including a horrific bus

accident and two years of recovery, he returned in 1989, beginning his search in the

city of Udaïpur. There he consulted a friend’s astrologer and soothsayer, who shed

light on his mission and put him in touch with two families of tantrika artists that were

creating Tantra paintings. Over the next few years, Jamme was introduced to a

number of different tantrika families throughout the state of Rajasthan and was given

permission to bring some of their works to Europe and America. Eventually he

collaborated with Hudson, founder of the New York gallery Feature Inc., to assemble

the collection of 71 Shiva Linga paintings that now form the Hudson Collection at

ICON.

When this series was exhibited at Feature Inc. in 2007, the gallery noted: “These

Shiva Linga paintings on found paper are created anonymously

by practitioners of Tantrism, some of whom are artists, to represent and embody

fundamental aspects of Tantra, a vast and complex spiritual and philosophical

practice. Made to awaken heightened consciousness, these devotional images are

used for visualization and meditation as part of Tantra’s spiritual practices. The

progeny of hand-written, illustrated religious treatises from the seventeenth century,

copied across many generations, the paintings seem both timeless and utterly

contemporary. They also possess a remarkable affinity with examples of twentieth-

century abstract art. . . . These paintings are part of a distinct visual lexicon that

confounds assumed differences between East and West, the spiritual and the

aesthetic, the ancient and the modern.”

Within the restrained iconography of the Shiva Linga motif, the paintings by certain

tantrika families appear to have a distinctive style. To a modernist sensibility, the

paintings from Udaïpur seem to be some of the most formally varied and are among

the boldest and most innovative works in the series. This exhibition highlights those

paintings.

The French poet and scholar André Padoux has described the anonymous Shiva

Linga paintings: “Artless, modest in appearance as they may seem, these lingas can

induce a vision of the infinite: painted silences . . .

the simple revelation of pure consciousness.”

Tantra Art from Udaïpur